Modular Rotary Valves Cut Costs for Mining Company Cement Plant

November 21, 2011

|

Sand House Crew at work during a sand pour. |

Operated by US Silver Corp., the Galena Mine in Wallace, ID was discovered in 1887, but major silver-copper and lead-silver production did not start until 1953. The mining operation involves drilling and blasting narrow-width, high-grade veins deep underground. The ore-laden rock is hoisted to the surface and transported by rail to the mill where it is crushed into powder. Metals are separated from the rock dust by a flotation process and then dried for shipping. The concentrates are shipped by truck and rail to Canada for smelting.

Early on, miners in the Silver Valley learned to mix cement with mill tailings (i.e. sand) to make cemented backfill. The Galena mine uses this backfill mix for some workings 2400 and 5200 feet below the surface. Cemented backfill provides a stable back (i.e. ceiling) for mining operations. “One of our mining methods is to work under cemented backfill rather than under native rock,” said Alan Gilda, Galena Mine engineer. “We prefer to have a layer above us that we know is stable.”

|

|

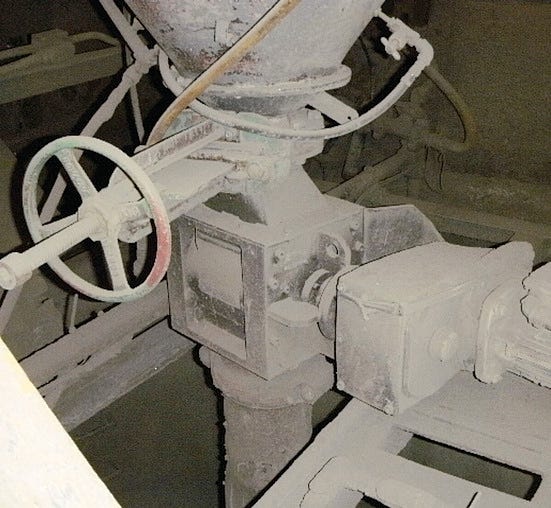

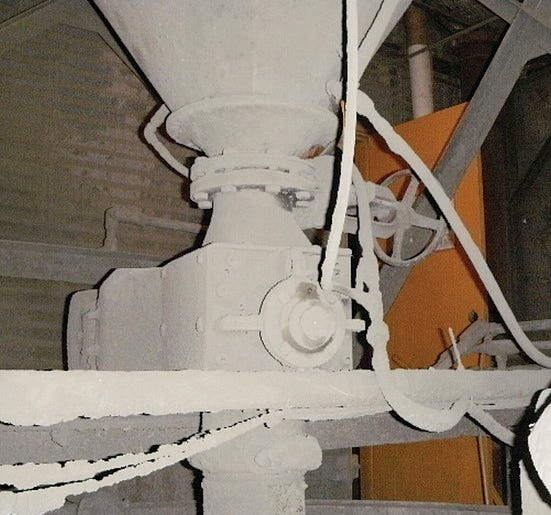

Figure 1: Cement plant rotary valve at the Galena Mine in Idaho |

The current cement plant was installed in the 1980s. Although the cement plant is not used every day, when production is needed, the mining operation depends on the equipment being ready and functioning as required. In a typical month, the plant must be able to run between 50 and 300 tons of cement.

A rotary valve is used to dispense Portland cement from a 60-tn silo into a large mixing tank, where water and mill tailings are added and agitated. Approximately two years ago the mine operator made the decision to replace the old rotary valve that had been in use since the beginning. The old valve was a cast unit that had already been repaired several times and had become so worn it would leak, making it difficult to control the mix. “We had trouble controlling costs because of this,” said Gilda. “We need to be accurate when we make the mix in order to ensure the concrete over our heads meets design requirements. The old valve was difficult to control and the excess concrete would wash out of the stope resulting in extra costs.”

|

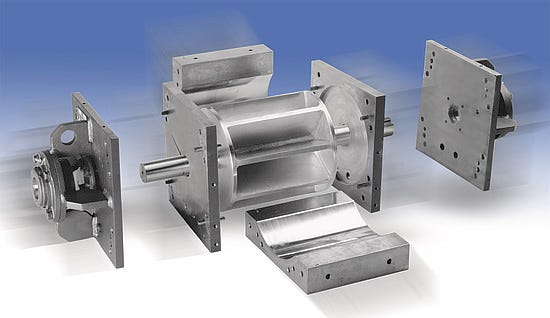

Figure 2: An exploded view of a Precision Machine and Manufacturing PMV valve |

Gilda’s research showed the costs to rebuild the old valve again versus buying a new one were comparable. He searched for new valve sources and whittled the list of companies down to three. Precision Machine and Manufacturing Inc. of Eugene, OR won the order because of its valve’s modular construction. With Precision’s PMV valves (see Figure 2), components of the valve can be replaced without having to remove it from the silo – which will prove to be a major labor-saving factor for the mine operator when the valve needs service. “With the old valve, we had to take the plant down while we swapped the valve out,” said Gilda. “Since the valve was in a location that was very inconvenient for our mechanics to access, it made the problem harder and increased our downtime.”

The other valves that Gilda evaluated were cast valves. They could functionally handle the job, but couldn’t be taken apart with the same ease and would require machining more often as their components wore. “With Precision’s valves, if you need to replace the rotor, the motor just swings out of the way,” says Gilda. “You can even turn the rotor around or flip the barrel sides top-to-bottom to expose new wear surfaces to the cement, extending the operating life of the valve and delaying the need for any machining or replacement of parts.”

|

Miners at work in a stope, a stepped excavation to mine steeply inclined veins of ore. |

Gilda highlights as another advantage of Precision’s PMV valves the fact that they employ direct-drive motor connections, eliminating potential pinch points that other chain-driven valves have. Gilda notes that Precision’s product was a little more expensive upfront to purchase than some of its competitors’ valves, but he anticipates the mine will come out way ahead over the life of the plant, because of the Precision valve’s easier and less frequent maintenance. So far, the valve is proving its worth because it has required zero maintenance since it was installed more than a year ago.

The more precise Precision Machine valve is also enabling the Galena Mine to save costs on cement. Plant operators do regular quality testing of the concrete they produce in order to ensure it meets or exceeds the minimum required strength. With the old leaky valve, the strength data varied a lot, so the plant operator continually added extra cement to the mix to make sure the batches were strong enough. With the more precise PMV valve, which is machined to a tolerance of .003 in. between rotor and barrel, cement can be metered into the mix with much more consistency. “With the Precision valve, we have much better control of the mix,” said Gilda. “Now we get a better product with just 12 or 13 tons of cement in the mix where we used to use about 20 tons.”

Precision Machine and Manufacturing Inc. (Eugene, OR) is a leading designer and manufacturer of precision rotary valves, feeders, and screw conveyor material handling systems and components. For more information, visit www.premach.com.

You May Also Like