EU Chemicals Exports Hurt by Emerging Market Collapse

A new report examines COVID-19’s possible long-term impacts on the chemicals industry in the European Union.

September 25, 2020

By Nigel Davis, Insights Editor, ICIS

EU chemicals trade has shrunk this year, as the coronavirus pandemic has spread and lockdowns have restricted industrial activity and consumer goods demand.

Trade is vitally important for the sector which has enjoyed a strong trade balance over the years. Chemicals has benefited hugely from globalisation and from broad-based tariff reductions.

A key question is how the pandemic will impact trade over the longer term. Through lockdowns, local production for local supply was of vital importance. Producers worked hard to supply and work with customers as best they could, but long trade routes came under particular pressure.

An underlying trend may be towards more local supply for local demand, although how that might be achieved in such an asset and investment heavy industry as chemicals remains to be seen.

For years, large companies have sought to produce from bigger, more efficient hubs, strategically placed to serve increasingly globalised markets. EU producers, large and small, have captured growth not just from developed world markets such as the US, but from emerging economies.

Emerging countries key

Pre-pandemic, future demand growth was very much tied to the health of the still developing economies, with Africa seen as ripe for growth.

While the EU continues tense trade negotiations with China, it is easy for focus to be drawn to the changing fortunes of, and the 27- country bloc’s relationships with, the world’s economic giants.

Thinking of fast-developing markets, however, the EU finalised this year a landmark trade agreement with Vietnam which has been enthusiastically supported by the chemicals industry.

The EU calls it the most comprehensive trade agreement the EU has concluded with a developing country. It gives Vietnam a 10-year period to eliminate duties on EU imports, although chemicals and pharmaceuticals are among the products that are already imported into Vietnam duty free.

The EU says that there is a strong commitment on both sides to environmental and social rights – a potential flash point in current talks between the bloc and China. A great job has been done in Vietnam containing the coronavirus outbreak, but the country’s economy has suffered terribly.

World Bank data shows its economy still growing at 0.4% in the second quarter, a rate described by the Bank as exceptional during the pandemic. But this was still the worst performance over the past 35 years. Vulnerable to new waves of coronavirus outbreak, Vietnam could be caught in a coronavirus economic trap.

What that trap might look like is as yet unclear, but it is likely to mean that demand for chemicals and the products made from them – or the products that Vietnamese companies might make from them - will be impacted, possibly severely.

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, in its Global Goals report published on Monday, looks at the health and welfare aspects of the coronavirus crisis.

In terms of vaccine coverage, said to be a good proxy for how health systems are functioning, it suggests we’ve been set back about 25 years in 25 weeks.

“One of the most important questions the world now faces is how quickly low-income countries can catch back up to where they were and start making progress again,” the report said.

“The hardest-hit will need support to make sure that what should be temporary reversals don’t become permanent.”

The point is that the health crisis has created an extraordinarily deep economic crisis which the poorer countries in the world – not simply the poorest – will struggle with for many years.

The projections are deeply concerning. Many millions have been pushed into extreme poverty by the crisis. Healthcare systems in the poorer economies are under extreme pressure. Most countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the lowest income part of the world, but one in which countries had been growing the fastest, cannot borrow the money needed to minimise the damage wrought by the pandemic.

And, as the report says, there is a cap on how much money governments can spend on the safety net.

“IHME [the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington] estimates that extreme poverty has gone up by 7% in just a few months because of Covid-19, ending a 20-year streak of progress,” the report added.

“Already in 2020, the pandemic has pushed almost 37m people below the $1.90 a day extreme poverty line. The poverty line for lower- middle-income countries is $3.20 a day, and 68m people have fallen below that one since last year.”

Re-evaluating chemicals

The loss of progress and the slump in living standards dramatically shifts the ability to consume now, as well as the consumption landscape over time.

It demands a re-evaluation of how chemical companies can best serve consumer demand, an assessment of just where that demand might be – and for what.

Clearly, chemicals demand growth is severely impacted by the coronavirus pandemic.

Economic stimulus by the rich nations will limit some of the impact, but innovation will be needed to help developing economies recover from the pandemic’s impact.

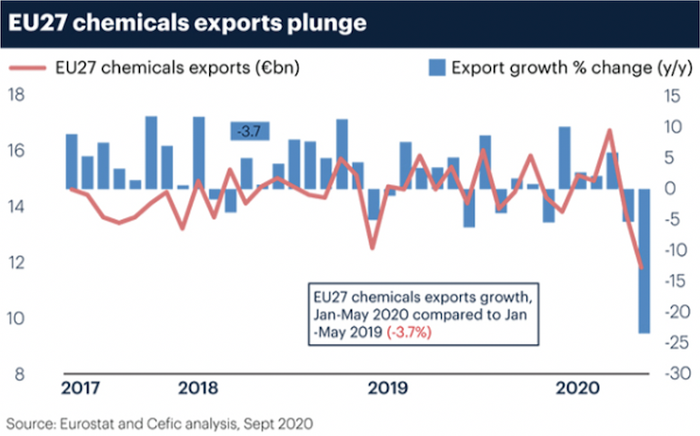

As far as EU chemicals trade is concerned, exports from the bloc were down $2.7bn in the first five months of 2020, at €72.4bn, with petrochemicals exports to the US up €2.3bn (or 8.8%) but a significant drop in exports of speciality and consumer chemicals.

EU chemical exports to China, of €6.3bn, were 1.2% higher than in the similar period last year.

“All in all, data on April and May showed two consecutive declines in extra EU27 chemical exports,” European chemicals industry group Cefic said.

“No clear sign of recovery is observed on the exports side.”

You May Also Like