February 17, 2016

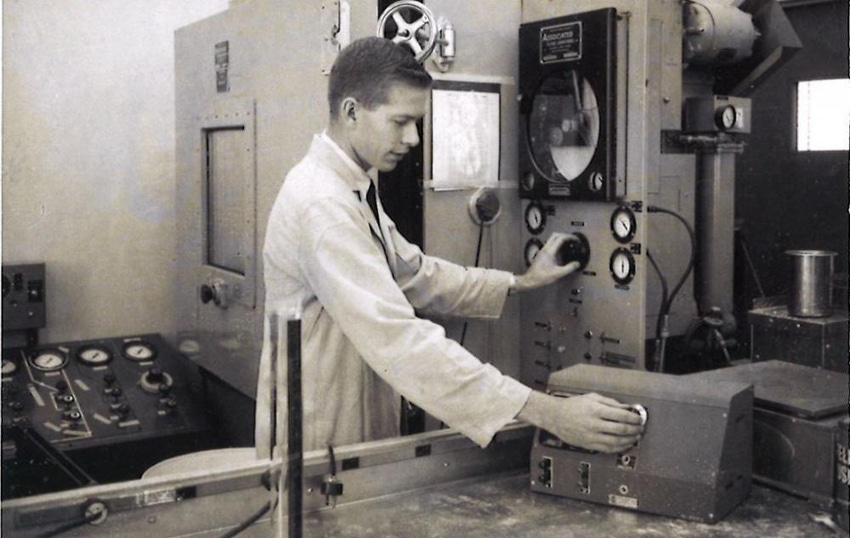

My exposure to the science and technology of bulk solids handling began while I was attending Northeastern University in Boston in the early 1960s. I was fortunate to be offered a cooperative education (“co-op”) job at US Steel’s Applied Research Center in Monroeville, PA, where I was assigned to their Bulk Solids Research group. This was a lively, interesting group of individuals led by Henk Colijn, with Dr. Jerry Johanson as chief researcher. I did research on loads acting on inserts in bins, friction plate sizing of bulk solids, and other topics.

Johanson left US Steel in 1966 to form Jenike & Johanson Inc. (“J&J”) with Dr. Andrew Jenike, his thesis advisor while at the University of Utah. I remained at US Steel to finish my co-op term, before graduating from Northeastern in 1967.

I had the opportunity to meet Jenike upon returning to Boston from US Steel, and he offered me a summer job between undergrad and grad school. The company was then located in the basement of Jenike’s house in Winchester, a suburb of Boston.

I attended grad school at MIT and completed my Ph.D. in October 1970. Upon graduation I joined J&J, and 45+ years later I’m still there!

Over the years J&J has opened six branch offices: Toronto (1975), San Luis Obispo, CA (1982), Chile (1994), Australia (2012), Houston (2013), and Brazil (2014). Currently we have nearly 90 employees, of whom more than half are degreed engineers. We offer a wide range of services in the field of storage, flow, and processing of bulk solids: testing, consulting, structural design, custom fabrication, capital projects, simulation and modeling, training, and forensic services.

The Powder Show

The first Powder Show was held in Rosemont, IL in May 1976. Its formal name was “International Powder & Bulk Solids Handling & Processing Conference and Exhibition” – what a mouthful! It’s no wonder everyone started simply calling it “The Powder Show”.

The organizer of the first show was Abraham Goldberg through his organization, Powder Advisory Centre, in England. Goldberg had organized similar shows in the UK, so it was natural to extend this concept to North America.

J&J was among the 60 or so exhibitors at the first show. There weren’t any short courses; instead there were technical sessions at which leading engineers in the field presented results of their research. Presenters came laden down with carousels of slides, as did some who were prepared to challenge their work. I vividly recall a few heated exchanges on technical matters.

The Powder Show fulfilled an unmet need. Remember that this was well before the days of the Internet -- and even before fax machines had been developed. Firms had to rely mainly on glossy brochures sent via snail mail or distributed by sales people to get the word out. The show provided a unique opportunity for people in industry to meet experts face-to-face and to see equipment in operation.

Goldberg continued to organize and run The Powder Show for a number of years. There’s no question in my mind that he was the driving force in making this the success that it became, and it is testimony to his work that it remains the premier conference and exhibition in this field even today.

Get more information or register for the Powder Show, May 3-5, 2016

After selling the Powder Show, Goldberg moved his family to Israel where he became a rabbi. He was involved in setting up educational facilities in Jerusalem to allow religious students to learn more about the secular world. Unfortunately, he died an untimely death in November 2014 when, along with three others, he was brutally murdered in a terrorist attack on a synagogue in Jerusalem.

Technological Changes

I have witnessed tremendous changes during the past half-century. When I began working in the industry, I performed all of my calculations on a slide rule. I drew Mohr circles and calculated angles of internal and wall friction by hand using a compass and protractor. Reports and letters were hand written. Then a secretary typed them using a manual typewriter. The letters “cc” literally meant “carbon copy”. Gradually, electronic calculators came into existence, as did word processors and unbelievable computer speed.

I’ve witnessed major changes in industry as well. Corporate R&D centers and central engineering departments have all but disappeared. Outsourcing has become a way of life. The demand for quality of products is greater than ever, and firms must be able to service a global marketplace if they hope to survive. New products and processes require pushing the envelope of existing technology.

The Future of the Industry

Looking forward, I am confident that the future is bright for those individuals who are currently working in this field and for those who will join in the future. I have four reasons for being optimistic.

Reason for Optimism #1: The Importance of This Technology Is As Great As Ever

Bulk solids handling is, by far, the world’s largest industrial activity and certainly one of the most mature, having been carried out for over 2000 years. It has been estimated that over 16 billion tons of common bulk solids are handled – often many times – every year. Yet, even with all this history and wealth of experience, far too many solids handling projects still go wrong!

When visiting clients I still hear words such as:

• “It’s just a bin.” (Downstream equipment often does not perform as intended unless the flow of material into it is uniform and reliable.)

• “There’s no need to design transfer chutes. We can modify them in the field.” (Field modifications are time consuming and more limiting than designing transfer chutes right the first time.)

• “The material was well blended, I just don’t know what went wrong.” (Most post-blend handling processes allow segregation events to upset a material’s uniformity.)

A strong reason for the lack of understanding about this technology is that education of engineers in this field isn’t much better than it was 40 or 50 years ago. We at J&J have been offering short courses in this technology through AIChE and other groups since the early 1970s. Despite the popularity of these courses, only a small fraction of engineers in industry receive such training. Most of the rest often flounder when faced with a bulk solids handling problem. This is even truer in developing areas of world, so they are ripe for introduction of this technology.

Reason for Optimism #2: There Are Many Unsolved Problems Needing Attention

The authors of a 2005 NASA paper observed:

Working with soil, sand, powders, ores, cement, etc., and using hoppers are so routine, that it seems straightforward to do it on the Moon and Mars as we do it on Earth. This paper brings to the fore how little these processes are understood and the millennia-long trial-and-error practices that lead to today's massive over-design, high failure rate, and extensive incremental scaling up of industrial processes because of the inadequate predictive tools for design.

In response my friend Lyn Bates, of Ajax Equipment, has been quoted as saying: Bulk solids technology is not rocket science – it’s much more difficult than that! What’s more, rocket scientists agree!

More robust and precise solution methods are needed to address some of the many common problems, such as ratholing, caking, segregation, silo vibrations, properties of – and design procedures for – unusual bulk solids, such as those that are anisotropic, both viscous and cohesive, or both elastic and cohesive. The number of problems to be solved is endless.

Reason for Optimism #3: DEM Is Providing Useful Insight into Complex Bulk Solids Behavior

Computer modeling using the Discrete Element Method (“DEM”) has come a long way since the turn of the century. Fifteen years ago the state-of-the-art was limited to spherical particles of varying size. Eight to 10 years ago, “gluing” spheres together to create clusters was introduced. Today, modeling of more realistic shapes using polyhedral particles is possible.

While this technology holds huge potential, it is still a long way from modeling most “real” systems. For example, the number of particles in an industrial-size silo is on the order of 1015, but current DEM codes are limited to on the order of 106 particles – nine orders of magnitude difference! At present the demands on computing power are impractical, particularly considering that the time scale is inversely proportional to particle size. Then there is the very real problem of particle cohesiveness, which has yet to be fully addressed.

One must guard against assuming that pretty pictures and videos that “look right” are sufficient to ensure that the results of a DEM run are correct. Furthermore, at best DEM can answer the question, “Why is this problem occurring?” but it cannot provide guidance as to what to change to correct the problem. This is where the expertise of design engineers who have worked in this field for years comes into play.

Reason for Optimism #4: There Is a Great Group of Committed Individuals around the World Who Want to Do the Right Thing and Are Passionate About This Field

I have been fortunate to know and work with many people both in academia as well as industry who have built this field to where it is today. Their contributions have been -- and they continue to be – substantial, as is their passion for this field. Given the continuing importance of bulk solids technology, the unsolved problems that need attention, the promise of new technologies such as DEM, and the enthusiasm and technical abilities of those who are following in the footsteps of giants in this field, I have great confidence that the future is indeed bright.

Dr. John W. Carson is president, Jenike & Johanson, Tyngsboro, MA. Besides being a founding member of AIChE’s Powder Technology Forum, he belongs to ASME, ASCE, and ASTM International, where he is chair of committee D18.24, “Characterization and Handling of Powders and Bulk Solids.” IN 2015, Carson received AIChE’s (American Institute of Chemical Engineers) 2015 PTF (Particle Technology Forum) award that recognizes lifetime outstanding scientific/technical contributions to the field of particle technology, as well as leadership in promoting scholarship, research, development, or education in this field. Carson is also a recipient of the Solids Handling Award, presented by The Institution of Mechanical Engineers (Britain) “in recognition of professional excellence in bulk solids handling technology.” For more information, visit jenike.com.

You May Also Like